The Workers’ Party (PT for it’s spanish acronym) of Paraguay – a non-hegemonic party with few resources – was subject of censorship by the Facebook social network, forcing the party to take measures to avoid loosing its right of free expression in the Internet.

The case

Last September, the Workers Party (PT) published an article addressing the imprisonment of Oscar González Daher- former senator and president of the Magistrates Trial Jury (JEM) – an unprecedented case in the country regarding seizure of an elected authority.

The article was published on the PT’s official website http://ptparaguay.litci.org/ and distributed on social media. Facebook is currently the most popular social network of the party, with more than 8,000 followers and a very active account that makes visible all the work of the organization.

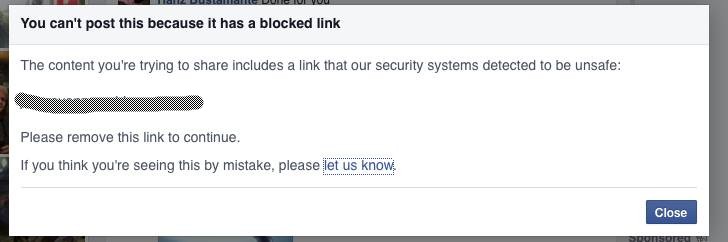

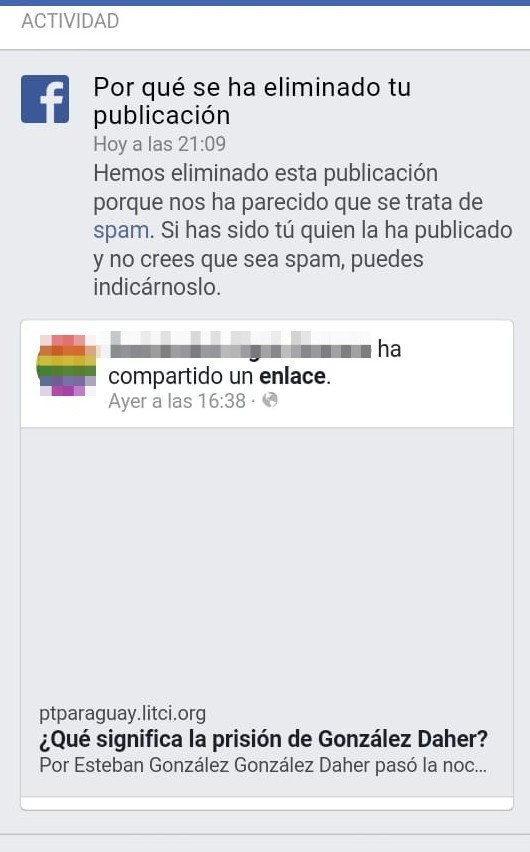

However, and to the great surprise of those involved, shortly after the note was published, both the article and the domain (address of the website) were classified as spam by the Facebook.

The above implies numerous problems: Once Facebook classifies a webpage as spam, it automatically stops being shareable in the social network, making it impossible to distribute any information contained in it and by any user of the network, both PT social media account and also third parties.

One step back: Facebook community rules and spam

Invoking principles such as security, equity and voice, Facebook makes available to different users its “Community Standards“, a set of -valga redundancia- community rules that describe what is allowed and what is not allowed on Facebook.

Section (IV) Integrity and authenticity, in its subsection 16 addresses spam and states that Facebook:

Strive to limit the spread of commercial spam in order to avoid false advertising, fraud and security breaches, which prevent people from sharing and connecting. We do not allow people to use misleading or inaccurate information to increase the number of likes, followers or times the content is shared.

It is important to recognize the efforts of Facebook to make transparent it’s content moderation processes. When establishing general community standards, it establishes game rules that must be known and respected in advanced. However, each case in particular must be studied, to avoid discretionality and not end up censoring certain speeches.

Transferring the application of community standards to the specific case of the Workers’ Party, it is worth analyzing a series of points related to the problem they faced, as well as the specific responsibility of Facebook when censoring a left political party (It is not being evaluated if there was a direct or indirect action by the platform):

- The website in question was marked as spam after a blog publication that directly attacked corruption, a cancer in Paraguayan democracy that is related to complex power threads of economic and political nature, and new actors like drug trafficking.

- There are no satisfactory mechanisms to appeal Facebook decisions once a web page domain is categorized as spam. Both in the Facebook help service and in the FAQ’s forum itself, users provide testimonies of how their domains were blocked without apparent explanation, and with no response from Facebook once they appealed the decision.

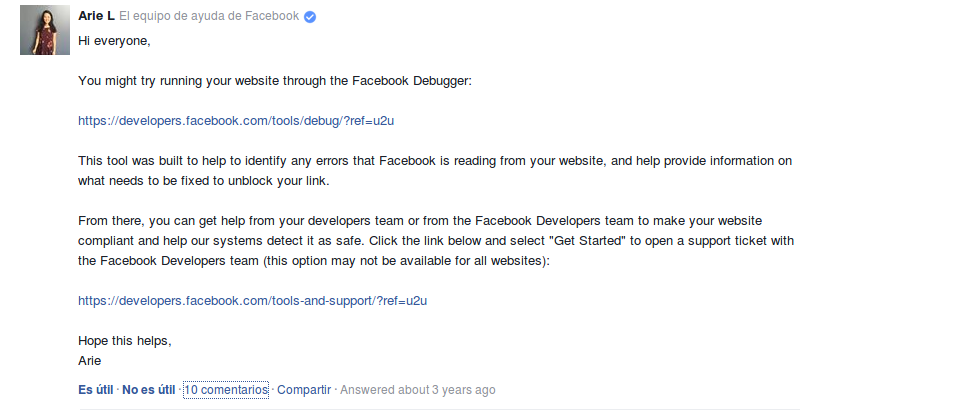

- The current Facebook Debugger service – helps to identify errors that Facebook reads from a web page in order to later solve them with a developer – has received numerous criticisms from users who have followed the instructions to hone their website according Facebook demands, to then still remained categorized as spam.

- From a user’s point of view, Facebook’s help service makes it very difficult to find information on what steps can be taken to declassify a web page as spam: Users complain in different countries about the problem, and the only official response found to date within the Facebook help service is to an English-speaking user. In the case of questions written in Spanish, no type of response is identified by the platform.

Freedom of expression in Paraguay and the Internet

“Free expression and freedom of the press are guaranteed, as well as the diffusion of thought and opinion, without any censorship, without more limitations than those provided in this Constitution: consequently, no law that makes it impossible or restricts it. There will be no press offenses, but common crimes committed through the press “

Freedom of expression is enshrined in the Paraguay’s National Constitution – article 26

At the international level, both the Human Rights Declaration and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights of United Nations recognizes the importance and the right to freedom of expression. Both instruments have also been ratified by Paraguay.

On the other hand, the United Nations Human Rights Council, at its 32nd session, explicitly addresses the relationship between freedom of expression and the online environment, by saying that:

“Affirms that the rights of individuals must also be protected on the Internet, in particular freedom of expression, which is applicable regardless of frontiers and by any procedure chosen, in accordance with Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights “.

Thus, freedom of expression is a widely recognized right both at the local and international level. Digital platforms that store and distribute content must take all necessary measures to ensure a free and safe exercise of this right, beyond specific precautions that they can decide as private patios that decide what type of content is not acceptable on their platform, i.e: nudity or sexual content on Facebook.

Lastly, freedom of expression in it’s interrelation with other rights such as access to information, free association and privacy, only further strengthen the importance of its full implementation in physical and digital environments.

Intermediary liability on third-party content

Intermediary liability on the Internet has a series of characteristics that determine precisely the degree of responsibility that is attributed -or not- to an intermediary about third party content.

Depending on the legislations of each country, the above varies. For example, Section 230 of the Communication Decency Act (CDA) of the United States explicitly states that:

“No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider”.

Thus, online intermediaries that store or re-publish discourse are exempt from a series of laws or approaches that could make them responsible for content published by third parties. However, the above does not mean full discretion on the part of private third parties: When carrying out explicit acts of content removal, the platforms must comply with human rights standards and, above all, allow freedom of speech and access to information of its users in the online environment.

On the other side of the pond, the e-commerce Directive of the European Union establishes that those responsible for content are the users that publish the content. Platforms are required to intervene or remove content only if they are informed of a specific violation.

There is no obligation to actively monitor users activity. However, this will have a paradigmatic shift with the adoption of the Copyright Directive and the controversial article 13, approved last March.

From Latin America, spaces for reflection that address the issue in a multi-stakeholder way are needed, in order to reflect best approaches to ensure online expression and a human rights perspective regulation. The debate around an approach that satisfies all the parties is far from being solved. It’s going to be an issue that will probably follow in a bidding of powers between different actors and interests of the Internet ecosystem.

Final reflections

Returning to the Workers’ Party case in Paraguay, a measure adopted by them to avoid Facebook blocking was, for instance, posting on their Facebook feeds links to their Twitter account in order to guarantee the circulation of the original post.

As a last resort, however, they were indirectly coerced by the platform to change their domain to a new one, in order to circulate their content organically in the main social network they are occupying.

The case described is of great concern for two reasons: One, the current way in which Facebook appeal system architecture is built, and two, the methodology in which the information is available to follow up cases that emanate from the Community Standards application, impact and make it extremely difficult to access information on various topics, including how to unblock a web page that was erroneously classified as spam. This must be solved urgently.

It is also worrisome that there is still a priorization from queries written in English (at least those that are immediately on the page). Not only is there a clear neglect of the platform in guaranteeing internationally recognized rights, but from a consumers point of view there is a silent discrimination on the part of this platform that must be immediately reviewed.

A final issue to be analyzed is how censorship not only impacts freedom of expression itself, but also, as a direct consequence, forces a small party to spend money to continue spreading its work. Resources that could be used to perform other types of important activities.

Returning to one of the initial points raised at the beginning of the article, some of the measures implemented by Facebook to generate a healthier ecosystem must be celebrate.

Their transparency policies that account for the way in which their Community Standards are being complied with by the company and the type of content they are pro-actively identifying and removing-depending on the case-are Facebook signals that, although responding to economic and maintenance of users interests, can guarantee a better environment to the entire community that inhabits the platform.

On the other hand, the application of these community rules – from a legal and operational point of view – still pose a series of problems that need to be thoroughly reviewed by the company: Cases such as the Workers’ Party, highlight the need to analyze each case with multidisciplinary perspectives in order to ensure a truly healthy online environment, where it is truly guaranteed that everyone’s voice is heard.

ABC of our community in 2023

ABC of our community in 2023  Worrisome regulation on disinformation in times of COVID19

Worrisome regulation on disinformation in times of COVID19